|

Emeritus Professor Peter Walls is a conductor, musicologist and consultant in the arts. He was Chief Executive of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra (2002-2011) and of Chamber Music New Zealand (2014-2019). Prior to that he was Professor of Music at Victoria University of Wellington (1994-2002) where he had taught since 1976, initially in the Department of English and then (from 1978) in the School of Music. Peter has held Visiting Fellowships at Exeter and Magdalen Colleges, Oxford (where he presented the Waynflete lectures in 2000), and at Clare Hall in Cambridge. |

A strange thing this symphonic repertory. From Tokyo to Lisbon, from Tel Aviv to Seattle, ninety percent of it is the same fifty pieces. The other ten is usually devoted to good-will performances of works by local celebrities. The rest is standardized. So are the conductors, the players, the soloists. All the units of the system are interchangeable. The number of first-class symphony orchestras in the world is well over a thousand. Europe, exclusive of the Soviet Union, counts more than two hundred. Japan alone is supposed to have forty. They all receive state, municipal or private subsidy; and the top fifty have gramophone and radio contracts. All musical posts connected with them are highly honorific. Salaries, especially for conductors and management, are the largest paid anywhere today in music. The symphony orchestras are the kingpin of the international music industry. Their limited repertory is a part of their standardization. The Appreciation Racket is a cog in their publicity machine.[1]

So Virgil Thomson railed against symphonic programming in 1939. He blamed the unadventurous character of symphonic programmes on collusion between conductors and orchestra managers and asserted that this had only an indirect relationship to audience preferences (‘the standardization of repertory, however advantageous commercially, is not a result of mere supply and demand’).

Little seems to have changed. Composers are still frustrated. As a strand within composers’ and critics’ complaints, the neglect of music by women composers has come into sharp focus. The problem is characterized as the dominance of music by dead white males on symphonic programmes. Since 2018, the website Donne: Women in Music has published an analysis of symphonic programmes. The most recent of these (examining the 2019-2020 season programmes of 15 major orchestras worldwide) pointed out that, across more than 1500 concerts, only 142 or a total of 3997 works (4%) were composed by women. Given, historically, the lack of opportunity for women to participate in most aspects of professional music, this 4% is essentially a subset of the contemporary music included in these programmes. The Institute for Composer Diversity was founded in 2016 ‘to encourage the discovery, study, and performance of music written by composers from underrepresented groups.’[2] The Institute takes a keen interest in the balance of orchestral programming. Incidentally, we should note that Thomson’s ’50 pieces’ supposedly monopolised 90% of orchestral performances. That left 10% for something else. But there is a strong inference that, ideally, the amount of music being performed by living composers should be a much higher proportion and, as a corollary, that music by women composers (and other under-represented groups) should be much more in evidence.

This is an essay about the factors influencing the formulation of symphonic programmes. It is about the conflicting perspectives of the symphony orchestra’s stakeholders (audiences, patrons, conductors, critics). Vocabulary is important: the same work might variously be considered as canonic, a masterpiece, seminal, a potboiler, a warhorse . . . this list could be extended. None of these terms is neutral. Each positions its user within a particular value system and all imply a hierarchy that influences informed choice. I shall begin with the tension between the aspirations of professional critics and popular taste before looking at the way in which statistical weightings (the force of numbers) make rebalancing the repertoire inherently problematic.

*****

In October 2019, The New York Times chief classical music critic, Anthony Tommasini wrote of a concert conducted by the Swiss conductor Philippe Jordan that

. . . for whatever reasons, [Maestro Jordan] returned with only the most standard of standard repertory: Prokofiev’s “Classical” Symphony, Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto and Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. Was there no contemporary work, a lesser-known score by a Swiss composer or even some overlooked piece from earlier eras that intrigued him? The challenge of such a program — or, to put it bluntly, the problem — is that these works are performed all the time and very well.[3]

A subscriber, a Mr Randel Cole, objected: ‘I have listened, usually painfully, to cutting edge or obscure compositions that you wish he had added to the program.’ He explained that what he wanted from a symphonic concert was ‘to be soothed and enthralled after a long day of tedium.’ There followed an exchange of views that the NYT printed under the headline ‘Is “Playing it Safe” Bad for Classical Music?’. Tommasini (picking up on the charge that, as a critic, he viewed these programmes through a different lens from audience members seeking respite from their daily lives) concluded his response with the claim that, ‘If classical music is going to have a future as well as a history then music-lovers and major institutions must foster new work. As a critic, I have a role to play in this effort.’ [4]

Looking to be ‘soothed and enthralled’ by classical music tends to be viewed with condescension by music critics and perhaps even more so by musicologists. Such limited aspirations attracted the scorn of Theodor Adorno. For Adorno, the slow movement of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5 in E minor represented escapism at its worst. He associated it with the nostalgic, sentimental and clichéd narrative that is the epitome of proto-cinematic kitsch:

a bright, moonlit night in the Crimea. The general’s garden, bright clouds, a bench, surrounded by roses. The pictures are tinted green. A well-built young officer with the noble, but also chubby face of the tenor, in full-dress uniform. Simply covered with medals on which the camera dwells. From time to time a star flashes on his chest. The scent he is wearing and his passionate courtship are conveyed by the melody on the horn. He is answered by the chaste and tender voice of a girl. The two have evidently already reached an understanding; there is no resistance. The officer falls on his knees before her. ‘I shall sacrifice everything for you – career, fame and even life and honour,’ He buries his head in her lap. A voice from the woodwinds, perhaps the South Russian nightingale, Tatiana by name, executes a mournful arabesque. The uniform with the medals is now photographed against the girl’s white dress. . . .[5]

Adorno’s disapproval takes on an ethical tinge:

It is doubtless true that towards the close of the nineteenth century the music that swept people off their feet did so because it combined drastic ideas with conventionality. In so doing it satisfied the demands of the cinema before the cinema was invented. It applied the techniques of cinema down to the very last details of its self-indulgent, butterfly mode of perception [my italics]. Thus Tchaikovsky’s backwardness . . . proves to be in advance of its time because it was part of the culture industry, even before the real consumers of the culture industry had come into existence.[6]

For Adorno, works like Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony were a ‘commodity’, part of a debased market economy.

If the performance of such music is somehow unworthy, the obvious question arises as to what orchestras should be playing (recognizing that ‘should’ takes us towards quasi-moral obligation). Here, the concept invoked by Randel Cole of looking at this through different lenses is relevant. Those who think of themselves as classical music lovers, on the one hand, and professional critics, on the other, often have radically different expectations and ambitions. The picture is further complicated by the priorities of conductors, orchestral artistic planning teams, and musicologists.

*****

Needless to say, Virgil Thomson didn’t ever compile a list of fifty works. His purpose in proposing one was purely polemical. It is nevertheless interesting as a thought experiment to try to construct such a list. Let’s start with what the ‘classical music lover’ might wish to include. There are, in fact, lists of the most-admired orchestral works, many of them emanating from broadcasting networks. Since 1996 the British Classic FM network has surveyed listeners annually to construct their ‘Hall of Fame’. They claim that this is ‘the world's biggest poll of classical music tastes!’ 200,000 voters each choose their three favourite pieces in order of preference. The published results list the top 300 works in preferential order. Table 1 gives the first 25 places from the latest round – together with the ranking these same works achieved in the previous three surveys.

Table 1: Classic FM Hall of Fame 2018-2021.

Interestingly, the list is predominantly orchestral. The median date is 1892. (Without Karl Jenkins’ Armed Man mass and John Williams’ theme from Schindler’s List – neither of them challenging, avant-garde works – the median date would have been 1880; taking Messiah – a pre-symphonic outlier – out as well would move the median date forward to 1886). Looking across four years, the survey seems to remix the same combinations.[7] There is very little churn. The works that failed to reach the top 25 in earlier years (here highlighted) were never far beneath that ranking. The table provides ample justification for thinking that popular taste circles around a very restricted repertory.

In New Zealand, the classical radio network RNZ Concert conducts an annual listener survey entitled ‘Settling the Score’ that produces a similar picture: The Lark Ascending occupies first or second position in most years. The London Philharmonic Orchestra under conductor David Parry issued a four CD set of (movements from) ‘The 50 Greatest Pieces of Classical Music’. While the selection was made by Maestro Parry and the LPO artistic planning team, they seem to have been shrewd judges of popular taste since the recording sold over 200,000 copies and held its position in the top ten classical albums on iTunes for over three years.

There are other surveys that are less focused on a freewheeling popular playlist in which Star Wars sits alongside Mahler 5 (‘includes “Death in Venice” Adagietto’). Even a specific focus on the symphony as a genre pulls such surveys towards more substantial works though it may also have an inherently conservative bias. Julian Horton noted that ‘reports of the genre’s demise have been regular, and usually involve complaints of anachronism, cultural redundancy or incompatibility with modern musical systems or expressive needs.’[8] In 2009 the Australian radio channel ABC Classic invited listeners to vote for their three favourite symphonies and, from that, ranked 100 symphonies in order of popularity.[9] Discover Music (Classic FM again) posted an article in 2018 with the title ‘These are factually the 10 best symphonies of all time’. ‘Factually’ is explained thus: ‘We think [my italics] these are the greatest symphonies of all time – the biggest, most emotional, most impressive and plain-old flabbergasting works ever written.’[10] Through an apparently similar process, France Musique produced a ‘playlist’ in July 2019 of ten works – ‘grand and epic classical orchestral symphonies that you should (re)discover post-haste!’[11] So, too, did Gramophone.[12] The BBC ranked ‘The 20 Greatest Symphonies of all time’ on their Classical-music.com website. This was compiled by asking 151 of the world’s leading conductors to submit their preferences. In late 2013 and the first half of 2014, The Guardian published (under the banner ’50 greatest symphonies’) music critic Tom Service’s survey of ‘the 50 symphonies that changed classical music’.

Table 2 shows the first twenty-five works in the ABC Classic list, comparing these to the other listener-recommendations mentioned above.[13] The shading indicates the basis on which these lists were compiled: pale grey for those voted by audiences (listeners), dark grey for conductor-determined lists and no shading for editorially constructed lists. The Guardian listing sits apart from the others because it represents the personal recommendations of a single critic and was, moreover, built primarily around works that were to be performed in the 2014 BBC Proms.

Table 2: ABC Classic FM's 25 most popular symphonies.

A few observations: First, we should note that all but two of these symphonies (Schubert ‘Unfinished’ and Mendelssohn ‘Scottish’) feature in the latest iteration of the ‘Hall of Fame’. Second, two thirds of the symphonies in this table have names or nicknames, making it easier for listeners to (a) recall and (b) characterize the works in question. This factor seems to provide buoyancy for the works that feature in more general popularity poll summarized in Table 1 (where only four entries are identified by genre and number alone). Third, these lists are remarkably consistent. Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 makes it into all the listings except the LPO’s ‘fifty greatest’, where the composer is nevertheless strongly represented). In this table of twenty-five works, only thirteen composers are represented (Beethoven four times). Fourth, the median date is 1876. Only one work was written after 1950 (eight symphonies across the entire array of 100 in the ABC survey).

Looking across the full ABC Classic 100 Symphony survey, the picture does not change. Table 3 summarizes the basic statistics. Only 33 composers make it on to the list, none of them women. In fact, Beethoven, Mahler, Mozart, Sibelius and Tchaikovsky account for over one third of the total offering. The 8/100 works premiered since 1950 is dismally fewer than the notional 10% seen by Virgil Thomson as reserved for contemporary works in orchestral programmes.

Table 3: Statistics drawn from the ABC Classic 100 Symphony survey.

The London Symphony Orchestra articulates its mission as ‘to bring the greatest music to the greatest number of people’.[14] The Philadelphia Orchestra ‘strives to share the transformative power of music with the widest possible audience’.[15] Such statements are typical. They acknowledge a need to be responsive to audience preferences, a need that no orchestra reliant on box office can afford to ignore. This is not purely a matter of ticketing revenue since institutional funders typically need the reassurance of healthy audience numbers as evidence that their investment is well placed. At the same time, state funders wish to see the prioritising of music by composers born or working within their own domains. Achieving excellent houses and promoting the work of living composers are not mutually reinforcing objectives.

*****

Popularity rankings have only an indirect relationship to actual orchestral programmes, which we should now consider. The League of American Orchestras conducts an annual survey of repertoire performed by US orchestras.[16] The most recently published of these appears to be the LAO’s reports on the 2010-2011 and 2012-2013 seasons.

Table 4 shows the number of performances by the top-scoring composers across two seasons. There are no surprises. Mozart and Beethoven vie for the top spot. Only three of the composers listed here were alive in the second half of the 20th century: Stravinsky (d. 1971), Shostakovich (d. 1975) and Aaron Copland (d. 1990). The only living composer to make it into the top fifty by performance numbers was John Adams (in place number 39). There are numerous single performances of works by living (and usually American) composers (these fitting Virgil Thomson’s scoffing characterization of ‘good-will performances of works by local celebrities’).

Table 4: Most frequently performed composers in the US 2011-2012 and 2012-13 seasons.

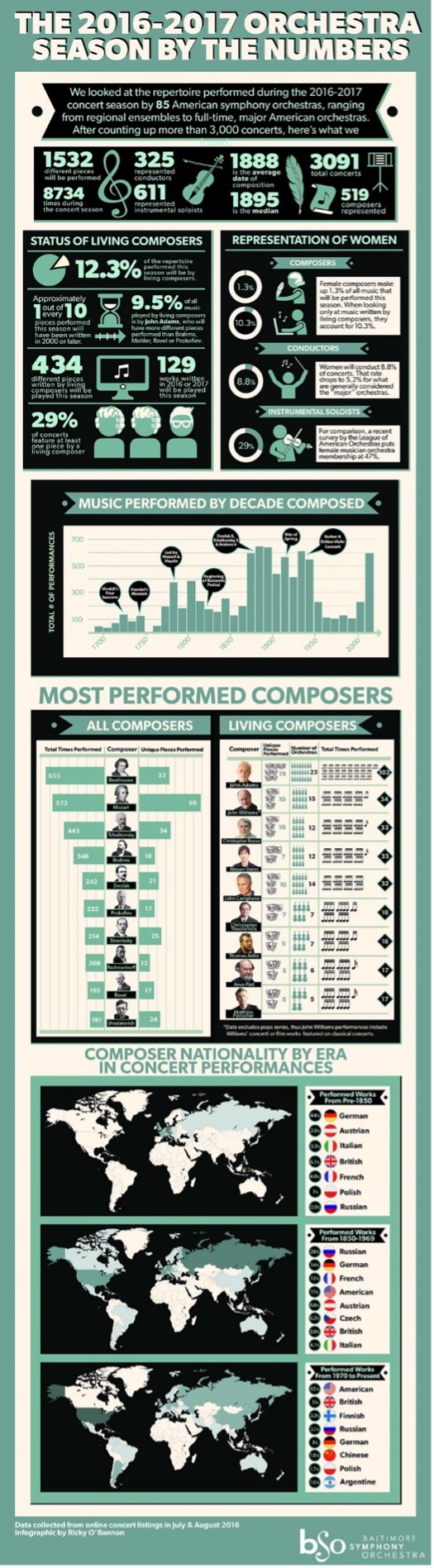

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra carried out its own analysis of programming in the USA for the 2016-2017. Their report includes a graphic summarising their findings (See Fig. 1).[17] The results are broadly consistent with the other surveys considered here: repertoire by living composers constituted 12.3% of the total, music by female composers 1.3%. Their hierarchy of most frequently performed composers gives the first four places to the same composers in Table 4 – with considerable overlap in those claiming lower-scoring positions.

Fig. 1: Baltimore Symphony Orchestra analysis of American orchestras’ programming for the 2016-2017 season.

The LAO listings are limited by compliance. The New Philharmonic apparently failed to submit a return for the 2012-2013 season (though they are represented in the 2011-2012 listings). As it happens, 2012-2013 was the inaugural season for Alan Gilbert as Music Director; Anthony Tommasini greeted their programme with the headline ‘Playing it Safe in Programming Philharmonic’. Tommasini did commend as ‘enticing’ one programme called ‘Three Americans’ that was to feature Bernstein’s Serenade, Ives’s Symphony No. 4, and a premiere by Christopher Rouse.[18] Ives and Bernstein were deceased; Rouse was the New York Philharmonic’s composer-in-residence that season.

As we have seen, Tommasini was expressing similar reservations at the end of the decade (again describing the orchestra’s programming as ‘playing it safe’). The New York Philharmonic’s 2020-21 season (not fully delivered because of Covid) would have featured no symphonies by living composers. The most-recently-composed symphony in the season was Shostakovich 10 (1953). There are only two Beethoven symphonies (perhaps because of the greater-than-average programming of Beethoven in the previous anniversary season). There would have been, though, two by Prokofiev (plus the concerto-like the Sinfonia Concertante), two by Mozart, two by Schumann, Brahms, Tchaikovsky and Sibelius. Eighteen out of the total of twenty-five symphonies feature on the ABC list. The most notable outlier is Barber’s ‘Symphony in One Movement’ (1936), but like most outliers, this one honoured a national composer. (For that matter, the ABC list included three symphonies by Australian composers – Ross Edwards, Philip Bracanin and Sean O’Boyle.)

We need to make some allowance for the conservative bias of the symphony as a genre. The NYPO had included a concert presentation of György Kurtág Fin de Partie (an opera based on Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, premiered in Milan in 2018). There were eleven works written by composers alive in the 21st century (including Dutilleux who had died in 2013). Numerically, this represents 13% of total works performed. Of these eleven, four were by women – part of the NYPO’s ‘Project 19’ (19 commissions to celebrate the centenary of the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote).

The Boston Symphony Orchestra’s 2019-2020 Season had a very similar profile. The main features are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5: Basic 2019-2020 Season Statistics NYPO and BSO.

The season offerings of other symphony orchestras (including the NZSO and APO in Aotearoa New Zealand), by and large, produced similar profiles – and their season announcements are greeted by music critics in articles that seem almost interchangeable.

The New York Times, having the luxury of a whole group of critics, invited each to respond to the NYPO’s plans for its 2020-21 season.[19] Every writer singled out for praise something a bit more ‘edgy’ than the repertoire dominating the surveys considered above. A few notable examples:

Joshua Barone: [The season] opens with the premiere of Ms. Montgomery’s piece for Project 19 [“Banner,” her stirring and cleverly political deconstruction of the national anthem].

Michael Cooper: It should be fun to hear what [Susanna Mälkki] makes of John Adams’s Saxophone Concerto.

Seth Colter Walls: Some of the Project 19 commissions feel like they’re thrown randomly into traditional programs. Not so with this more coherent bill, in which the Finnish conductor Hannu Lintu leads an evening that includes two touchstones by Sibelius, as well as the American premiere of a new work by the Icelandic Ms. Thorvaldsdottir.

Anthony Tommasini: I never would have imagined getting excited over a program offering two overplayed Tchaikovsky works: the First Piano Concerto and “Pathétique” Symphony. But the performers here [Manfred Honeck and Beatrice Rana] make all the difference.

We’ve already seen that the average audience member does not necessarily share these views. But what critics have to say is hugely important to orchestral managements. Having a respected critic in a major newspaper talk up your season, praising it for innovation and exciting programs, has an impact on subscription numbers and sales. Orchestral programmers walk a tightrope between the goals of trying to win critical approval and appealing to a broad (and often musically-uneducated) audience.

*****

Even more interesting than the extent to which orchestral programming reflects popular taste is the extent to which it doesn’t. ‘Popular classics’ – the theme from Schindler’s List, the Intermezzo from Cavalleria Rusticana, even The Lark Ascending – are not heard live in the concert hall all that often. It seems that the main concert series of major orchestras invariably favour a more serious segment of the repertoire – being dominated by substantial works that have come to be regarded, rightly or wrongly, as worthy of inclusion not just because of their popularity but because of some more deep-seated inherent artistic worth. To put this binary in its crudest form (hi-brow vs. low-brow), Classic FM’s ‘Hall of Fame’ seems brazenly to challenge the concept of the canon.

The ascendancy of an aesthetic in which autonomous works of art were revered and regarded as canonic coincided with the emergence of the orchestra as a fixed institution (with a structure so replicable that the instrumentation for any work may be summarised through the quasi-mathematical formulae that fill the pages of David Daniels’ wonderfully-useful Orchestral Music: a Handbook (or now, Daniels Orchestral Music Online).[20] Allied to this was the Werktreue concept (the ethical imperative that performers respect the essence of a musical work). In her important book on the emergence and regulatory force of this concept, Lydia Goehr invokes Liszt’s vision of an annual assembly ‘by which all the works that are considered best in these three categories [religious, dramatic, and symphonic music] shall be ceremonially performed every day for a whole month’.[21] It would not be too much of a stretch to say that every major orchestra’s subscription season honours that concept – the presentation of major works that are considered important in the history of music or as a statement about contemporary culture. The commitment to a serious artistic mission that went beyond mere entertainment was renewed in the foundation of so many major orchestras in the second half of the 19th century. The persistence of a reverence for the canon in the 21st century is evident in the desire of so many music directors and chief conductors to present complete cycles of symphonies by Beethoven, Mahler, Brahms, Sibelius, Shostakovich or Nielsen (in something like that order of preference). The canon is not just has a hierarchy of works but of genres too.[22] This, too, had an impact on the overall shape of orchestral programmes (leading eventually to the dominant overture-concerto-interval-symphony matrix of our era). It has never been the case that orchestras have performed only canonic works, but the wider repertory has often qualified for inclusion in concert programmes (the repertory) through proximity to the canon. (Without Rossini overtures, how would we understand the joke in the second movement of Beethoven’s 8th Symphony?)

The new aesthetic meant that the repertoire available to orchestras has grown steadily. In his seminal 1983 article on the canon, Joseph Kerman explained:

In previous centuries the repertory consisted of music of the present generation and one or two preceding generations; it was continuously turning over. . . . After around 1800 or 1820, however, when new music entered the repertory, old music did not always drop out. Beethoven and Rossini were added to, not replaced. Increasingly music assumed a historical dimension; music assumed a history. There were even attempts to extend the history back into an evanesced past.[23]

Kerman is right, of course, though we do need to acknowledge that a huge amount of repertory has, in fact, fallen by the wayside. In some cases, this may turn out to be only temporary neglect. The rediscovery of the orchestral music of Louise Farrenc (1794-1865), for example, seems under way. Nevertheless, this keeping current of an historical (and expanding) corpus of orchestral music means that those who complain about a decreasing proportion of music by living composers in concert programmes have statistical inevitability reinforcing their lament. As symphonic repertoire grows, the proportion of the total available repertoire occupied by music by living composers decreases. Table 6 (based broadly on listings in Daniels) plots the number of still-current works by living and dead composers from the era of Haydn and Mozart to the end of the twentieth century.[24] It illustrates that within an expanding corpus of ‘available’ repertoire there is an inexorably diminishing proportion of music by living composers.

Table 6: The growth in total available orchestral repertoire from 1780 to 1990 divided into living and dead composers.

It is salutary to note in 2022 that composers whom we might still think of as contemporary – Luciano Berio, Eliott Carter, Henryk Gorecki, Peter Maxwell Davies, Oliver Knussen to name a few – would now feature in an updated version of this table as ‘dead’ composers. Anyone trying to rebalance the proportions of music by living and dead composers in the repertoire has the inevitability of statistical evolution against them.

As with the literary canon, the musical canon is, to quote the literary critic M. H. Abrams, ‘the product of a wavering and unofficial consensus; it is tacit rather than explicit, loose in its boundaries, and always subject to changes in its conclusions.’[25] Literary theorists in the 20th century were often intent on canon-bashing or ‘opening the canon’. In one sense, Virgil Thomson’s challenge might be read as a cry for opening up the performing musical canon – but it has a special urgency since what is at stake is creating enough space within concert programmes for new composers to have their works heard.

*****

For a general audience, part of the problem with new music is its unfamiliarity. Given half a chance, the feared music of a living composer becomes a revered element in the repertory. Edward Rothstein published an opinion piece in 1982 (when he was still chief music critic for The New York Times) in which he commented on the gulf between the minority new music enthusiasts and the ‘mainstream’:

. . . despite efforts by Stockhausen, Cage and their modernist predecessors, the musical mainstream has remained relatively untouched by ‘avant-garde’ hands. The musical world has neatly split into two parts, each blissfully irrelevant to the other: the 19th-century performance culture and the culture of the ‘new’. The performance culture repeats its repertory; the culture of the ‘new’ has its own new-music audiences, new-music performance groups, new-music patrons, new-music journals and new-music recording companies – all with minimal influence on the bourgeois tastes and audiences that have been the traditional opponents for the ‘avant-garde.’[26]

Rothstein, invoking Nicolas Slonimsky’s Lexicon of Musical Invective,[27] pointed out that music now recognized as great has frequently been treated with suspicion and hostility by its first audiences (and critics). He took perverse comfort from a 1916 essay by Charles Villiers Standford who railed against modernist composers whose works are now entrenched in symphonic repertory:

[Stanford] referred to the ‘charlatan’ composers, the ‘professors of the confidence trick’. He included ‘A Classified List of Some “Futurist” and “Modernist” Composers.’ The 1916 list mentioned Albéniz, Chabrier, Debussy, Ravel, Bruckner, Mahler, Strauss, Rimsky-Korsakov, Scriabin, Rachmaninoff, Grainger and Grieg. A symposium followed, on the subject ‘Will the Music of Ultramodernists Survive?' These ultramodernists, of course, have since settled into our repertory, suggesting that someday the music of Webern and Boulez will also become comforting to audiences. The failure of the “new” to transform the mainstream then, would be just temporary, an indication of sluggish audience taste.

If facilitating the progression from alienating difficulty to comforting familiarity was what mattered, then persistence in programming new music (and especially ensuring that newly-commissioned works are re-programmed after their premieres) would address the problem.

Unfortunately, that seems too simplistic. The best-known offspring of familiarity is contempt – so evident in Adorno’s attack on commodity music noted above. Within the orchestral programming framework, a serious-minded commitment to canonic works more often than not coexists with an acknowledgement of the need to be programming new music – particularly by composers whose artistic and educational credentials provide some guarantee of symphonic literacy and interest. In 1958, Milton Babbitt argued that serious composers should not expect, or even look for, audience acclaim. Calling his essay ‘The Composer as Specialist’, Babbitt argued that modernist composers were exploring areas that might find a parallel in the work of scientists whose research took them into areas that only other scientists could be expected to appreciate.[28] Famously, Hi Fidelity magazine replaced Babbitt’s title with ‘Who Cares if you Listen?’ In 2006, Babbitt told the Princeton Alumni Weekly, ‘Now obviously, I care very deeply if you listen. From a purely practical point of view, if nobody listens and nobody cares, you’re not going to be writing music for very long. But I care how you listen.’[29]

*****

Programming an orchestral season might be seen as attempting to establish an equilibrium among competing claims. A typical season, while being responsive to popular taste, will be oriented towards substantial, ‘serious’ works – works that often have canonical status. It will also strive to find approval from critics, who have an influence even on those who think they are looking to be ‘soothed and enthralled’. It will include – and highlight – new music, particularly music by national composers. Because of the statistical imbalance between old and new in current repertoire, and because of the perceived difficulty for general audiences in coming to terms with cutting-edge new work, the amount of music by living composers typically represents a small proportion of the total offering. Moreover, the attention given to national composers all too often has the effect of crowding out music by other internationally acclaimed living composers. It will attempt to please (or placate) various stakeholders: a subscription audience (whose preferences are tracked through sales history), critics (who by and large feel honour-bound to resist stagnation), funders (who, in the case of state funders, have a strong interest in supporting local composers), conductors’ (especially music directors’) ambitions, lobby groups (Donne, the Institute for Composer Diversity). And it will be constrained by the structural inertia of the orchestra as a standard instrument (the inconvenience/cost of programming works that depart from the standard configuration of woodwinds, brass, percussion (etc.) and strings).

From a musicological perspective, programming provides fertile ground for examining various kinds of agency. What orchestras perform is never the product of unfettered artistic choice. If the overall picture looks similar (depressingly so, even) to the situation that Virgil Thomson so deplored nearly a century ago, I would nevertheless assert that discussions about programming within the orchestral world are, for the most part, driven by conviction and idealism. This is often led by enlightened music directors – but with the full support and active participation of professional artistic planners. With rare exceptions (the BBC Proms’ ‘Last Night of the Proms’ would be a standout example within a predominantly forward-looking festival), programmes are rarely led entirely by popular taste.

I make this claim on the basis of a personal involvement in orchestras and orchestra management (notably as Chief Executive of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra from 2002-2011). How to demonstrate it is more problematic. Listing initiatives around the world to increase the proportion of new music, music by women composers, music by indigenous composers etc. has a kind of centrifugal effect. And describing strategies that I have deployed to this same end seems self-indulgent. I might instead conclude by quoting from an interview with the conductor, Susanna Mälkki, who, as Music Director of the Ensemble Intercontemporain 2006-2013, has impeccable credentials in relation to the performance of new music and modernist classics. While Chief Conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic and Principal Guest Conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, she reflected on her own programming history and ambitions:

A lot can be done simply with programming, by putting different things together. . . Speaking of large-scale projects, yes it would be fun to do the Mahler Eighth too, some day. And while I’m forever defending the hard-core modernism, the so-called ‘greatest hits’ are awesome too. For example, I have a soft spot for Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances. I just love these pieces and one day I will certainly do a lot of them within one programme. These pieces are ‘hits’, of course, but they have become that because they are also such great music. What matters is respecting the music’s innocence and enabling contrasting experiences. During my Helsinki years, I’ve also programmed composers such as Elgar: well-known names, by whom most of their works are still mostly unknown over here. This kind of intention of proposing discoveries will continue, once we get into the large orchestra mode again. Still, there are good reasons why Beethoven and Brahms are so often played. Their music is simply essential.[30]

[1] Virgil Thomson, ‘Why Composers Write Now, or the Economic Determinism of Musical Style’, from The State of Music (1950), reproduced in A Virgil Thomson Reader (Boston: Houghton Mifflin: Boston), 122-147, p. 141.

[2] https://www.composerdiversity.com/about.

[3] New York Times 31 October 2019 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/31/arts/music/new-york-philharmonic-review.html.

[4] New York Times, 6 December 2019 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/06/arts/music/philharmonic-critic.html.

[5] Theodor W. Adorno, ‘Commodity Music Analysed’ in Quasi Una Fantasia: Essays on Modern Music, translated by Rodney Livingstone (London & New York: Verso, 1998) 37-52, p. 41f.

[6] Adorno, ‘Commodity Music Analysed’ (see note 4), p. 42f.

[7] Note that I have given a somewhat arbitrary first performance date of 1820 for the Allegri ‘Miserere’ since that is approximately the date at which the version that has become so popular became available.

[8] Julian Horton, The Cambridge Companion to the Symphony ed. Julian Horton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013) p. 2.

[9] See ‘Classic 100 Symphony’, Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classic_100_Symphony#Programming (accessed 20 May 2020). This was part of a series of such ABC surveys.

[10] See https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/latest/best-symphony/. Accessed 20 May 2020.

[11] See https://www.francemusique.fr/en/playlist-list-legendary-classical-symphonies-you-should-discover-or-rediscover-without-delay-22192. Published 2 July 2019; accessed 20 May 2020.

[12] See Gramophone 30 April 2014 https://www.gramophone.co.uk/features/article/top-10-symphonies; accessed 20 May 2020.

[13] An asterisk is used where no specific ranking is given for the works included in the list.

[14] https://lso.co.uk/more/news/1203-press-release-london-symphony-orchestra-2019-20-season-announced.html.

[15] https://www.philorch.org/your-philorch/meet-your-orchestra/

[16] League of American Orchestras Orchestra Repertoire Report, https://americanorchestras.org/learn/artistic-planning/orchestra-repertoire-report/ accessed 24 August 2021.

[17] Ricky O’Bannon, ‘By the numbers: The data behind the 2016-2017 Orchestra Season https://www.bsomusic.org/stories/the-data-behind-the-2016-2017-orchestra-season/

[18] Anthony Tommasini, ‘Playing it safe in programming Philharmonic’, New York Times 4 March 2012.

[19] ‘The Philharmonic’s New Season: What We Want to Hear’, 12 February 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/12/arts/music/new-york-philharmonic.html

[20] David Daniels, Orchestral Music: A Handbook, first published London: Scarecrow Press, 1972. This went through five print editions before emerging as Daniels’ Orchestral Music Online (daniels-orchestral.com).

[21] Lydia Goehr, The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), p. 205.

[22] On the hierarchy of genres implied by the canon see Weber, p. 334.

[23] Kerman, ‘A Few Canonic Variations’ (see note 6), p. 110-11.

[24] The table is generated from a somewhat arbitrary list of works by those who might be considered ‘major composers’. I believe it makes a valid point, though I would not wish to defend more than the overall picture. I used a terminal date of 1990 because of the difficulty of deciding whose works among those of our contemporaries will endure in the repertory.

[25] M. H. Abrams, A Glossary of Literary Terms, 7th edition (Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace), p. 29.

[26] Edward Rothstein, ‘Does music have an avant-garde?’, The New York Times 15 July 1982, page C17, https://www.nytimes.com/1982/07/15/arts/critic-s-notebook-does-music-have-an-avant-garde.html.

[27] Nicolas Slonimsky, Lexicon of Musical Invective (New York & London: Norton, 1953, repr 2000).

[28] Milton Babbitt, ‘Who Cares If You Listen? (1958)’ in Source Readings in Music History, edited by O. Strunk and L. Treitler (New York and London: Norton, 1998) pp. 1305-10.

[29] Elaine Barkin, Martin Brody, and Judith Crispin, ‘Babbitt, Milton.’ Oxford University Press, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002256107 accessed 7 September 2021.

[30] Jari Kallio, ‘For me, it’s not about being radical – interview with susanna Mälkki’ https://jarijuhanikallio.wordpress.com/2020/08/08/for-me-its-not-about-being-radical-interview-with-susanna-malkki/

Philip Auslander, Professor of Performance Studies and Popular Musicology at Georgia Institute of Technology, offers a new and different account of John Cage's infamous work 4'33", drawing on his recent study of "musical persona".

Nathan Dougherty, of Case Western Reserve University, explores the now largely forgotten genre of the romance and its significance to nineteenth-century French audiences and performers.

A doctoral student at UC San Diego, Keir GoGwilt presents his ongoing research into historical performance pedagogy, focusing on the eighteenth-century Italian professor Francesco Galeazzi and the art - or is it science? - of violin performance.

Musicologist Maribeth Clark explores how the song of a hermit thrush - heard while driving through mountains in southwestern Vermont - fascinated musicians and non-musicians alike in the nineteenth century.